People often talk about the “Bell curve” – a statistical distribution among a population of any property, such as athleticism, natural longevity or various kinds of intellectual ability. For most such properties, the great majority of people are located fairly near the mean. As you go further away from this mean value for any given property, the percentage of people represented tends to drop off precipitously.

That is one reason we are so astonished when one person is far from average in two properties at once – because it is quite rare. For example, there just aren’t that many astonishingly beautiful people who have also made groundbreaking and fundamental innovations in technology, such as Hedy Lamarr, or extraordinarily talented actors who have also had a nearly off-the-chart high IQ, such as Judy Holliday.

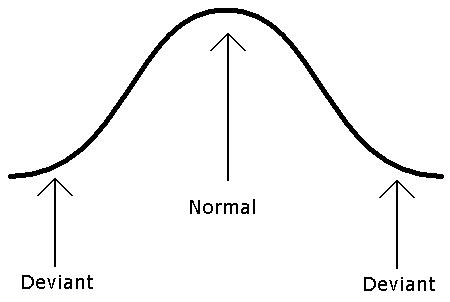

I don’t particularly like the image of the Bell curve (or as the Little Prince would say, a snake swallowing an elephant), because I think it tells the wrong story. A Bell curve visually suggests that in the center are the “normal” people, thereby implying that all the people who are far from the center are somehow deviant. I think this way of thinking misses the point, because it focuses on the middle – the boring part – rather the two ends, which is where things are most interesting.

I think it is better to embrace the two ends – rather than marginalizing them. For example, if I were extraordinarily nearsighted I would want society to help me to find ways to see better without subtely placing me in some marginal category because I am not like everyone else. The same would be true if I knew a child with a learning disability. I would want society to honor that child as an individual, by coming together to help her reach her maximum potential.

Similarly, a high intellectual ability in some area should be seen as a call to service. A talented artist or musician is fortunate, not because they are “better” but because they have a unique opportunity to enrich the lives of those around them. Similarly, those of us who either have or acquire an ability to teach or to do research have a responsibility to others, because we are in a good position to lend a helping hand to those around us in a particular way: Every ability you possess provides an opportunity to serve others, not an opportunity to imagine yourself superior to others.

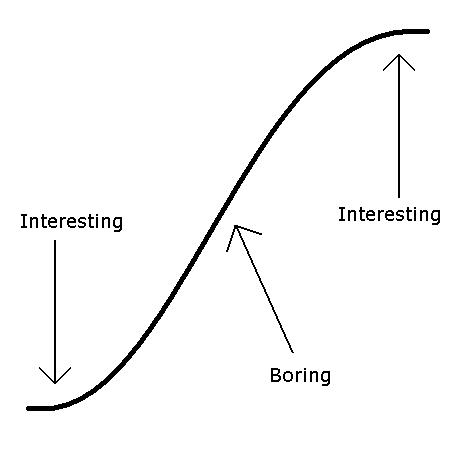

For this reason, I prefer to replace the Bell curve by a set of S curves, to visualize the ways that each of us may need a helping hand in some way, as well as the ways that we may be in a greater position to lend a hand to others. Each of us, every individual, finds ourselves on not one but many S curves, and we are most interesting for the ways that we are either to the left or the right on any given one.

Every once in a while I see an interesting (and fun) sign that somebody is at the extreme of some S curve. For example, today my sister Joan told me about a conversation she’d had just this morning, during a car ride with my eleven year old nephews Jack and David. They were all discussing the fact that today, June 21, is the longest day of the year (at least here in the northern hemisphere). The boys pointed out that there must therefore be a shortest day of the year. When Joan quizzed them on when that day might be, they quickly realized that it must be a hundred eighty two and a half days away – exactly half of three hundred and sixty five days.

As Joan was telling me this story, something started nagging at the back of my mind. It wasn’t the fractional day – that was ok. Rather it was the assumption that a year has 365 days. That is not quite right, since it doesn’t take into account leap days. I told myself that I was probably being hopelessly nerdy, and that I should just be pleased that my two wonderful nephews where discussing science and fractions with such ease and facility – not to mention avid interest.

But then Joan got to the end of her story. She told me that toward the end of the ride Jack became rather quiet, and she could tell that something was bothering him. She only realized what it was when they got out of the car, and Jack turned to her and declared, correcting his earlier statement, “A hundred eighty two days and five eights”.

My first thought when I saw the S-curve (without having read the blog entry) was: learning curve. This is exactly how I feel when I pick up a new topic.

Initially it’s all hot, shiny and exciting. Then it turns into labour… and all of a sudden (if I persevere) it’s all fun and interesting again since it opens new possibilities.

Granted, it’s probably more like a series of S-curves.

Cheers,

Mike

Thanks Mike, that is a wonderful observation! I completely agree with you. The two most interesting places to be are mystery and mastery. Everything else is a journey between them.

And as you point out, not necessarily a one-way journey, since mastery of a topic can open up an opportunity to explore ever more mysteries.