William Butler Yeats once said that “Education is not the filling of a bucket, but the lighting of a fire”, a sentiment with which I wholeheartedly agree. But what does it take to light a fire?

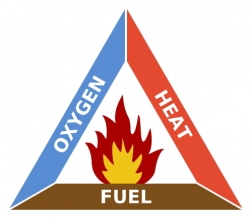

People who study the science of fire and combustion have an image for what it takes to light a fire, called the “fire triangle”:

For a fire to start — and to continue burning — all three of these components are necessary. But what is the “fire triangle” of learning?

I would argue that the fuel is intellectual curiosity, the oxygen is the sense one has that what is being learned is relevant or meaningful, and the heat or spark is the excitement that comes with true learning. When you look at learning this way, you can see much of what is wrong with our current approach to education, as well as what we might do to make things better.

If a student is told to sit in a classroom and learn something just because “it will be on the test”, then the student is being asked to learn in a vacuum. Without the important questions of “Why am I learning this?” or “What will I be able to do or think about or feel or express after I have learned it?”, then learning cannot really happen.

Yes, a student can be made to memorize, to learn tables of names and numbers and repeat back concepts by rote, but that is not true learning. The flame that Yeats spoke of is a flame of excitement, and that excitement is kindled only when a learner’s inherent curiosity and desire to explore encounters some sort of meaningful context, some interesting space to explore.

But what about the spark? Some students, but only a few, carry with them their very own tinderbox, and those students are very lucky. They have the ability to look at something they do not yet know, and see how their own curiosity will be set ablaze by the promise and implications of this new topic. There was probably little one could have done to prevent Mozart from composing, or Austen from writing, or Ramanujan from creating cathedrals of mathematical beauty.

But most people need a little help to find that spark, and that is where a good teacher is essential. A teacher’s love and passion for a subject is most often the single most important factor in kindling a student’s excitement for that subject. Good teachers know this, and realize, on some level, that they are indeed the keepers of the flame.

So if you’re a teacher (and everyone of us is, sooner or later), go out there and help light some fires!

thank you

You’re welcome! 🙂

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled.” ~ Plutarch

Yes, Yeats’ version has the very useful quality of pithiness, but not so much of conceptual originality. As far as I’ve been able to to determine, what Plutarch actually said is something like this:

Didn’t know it was that long. Quotes taken out of context without explaining sound often so much nicer. Just put it there to show that most smart things someone said in modern times has been said already by a greek 2000 years ago.

Yes, I completely agree. Thanks for providing the more complete reference chain. Ah, the value of good teaching! 🙂

As someone who studies games for learning, what would you say is the fire triangle for gaming? Does the concept of the fire triangle help relate gaming to learning? I got to thinking about this after reading this post because when I was a kid I used to love playing games (especially board games). I couldn’t get enough of them. As an adult I find that I don’t usually have a lot of patience for them. Now I get the kind of intellectual satisfaction that I used to get from playing games from constructing and debugging computer programs (for a similar amount of intellectual effort), and the payoff in relevance and meaning is a lot higher. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts.

Please, PLEASE stop attributing this “quotation” to Yeats! He never said it – not anywhere in his poems, plays, essays, speeches, letters, diaries, or notebooks. While I agree with the principle this maxim expresses, I don’t think we need teachers or students glibly “quoting” things from great writers as if they’d read the original work…especially when the supposed original work does not exist. What Yeats actually said was enough; let’s not put words in his mouth.

Thanks for that clarification. Though I’d my finger on my lip, What could I but take up the song? 😉