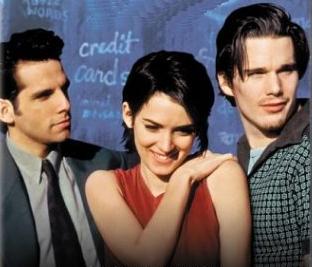

On a whim I went on-line and watched Ben Stiller’s directorial debut “Reality Bites”, which I had not seen since its opening weekend in 1994. At the time I had enjoyed it, but I hadn’t fully appreciated what Stiller and his partner in crime, screenwriter Helen Childress, were really up to.

On the surface the film is a Gen X take on an age-old romantic triangle. Disaffected young post-college cute girl caught between two guys. One guy is a useless, fickle, completely self-absorbed loser/slacker hottie, the other a kind, sweet, supportive, loving, successful not-as-hottie. So which one turns out to be Mr. Right, her one true love?

Since this is a Hollywood movie, there is only one right answer to this question. Hint: the first guy is played by Ethan Hawke, the second by Ben Stiller himself. Of course she realizes that her one true great love is loser/slacker Hawke.

After all, this was still 1994. Audiences were not yet ready for the sexy-as-hell ICW (Irresistible Child-Woman) to choose Zach Braff – “Garden State” was still a full decade away. Wynona Ryder’s job was to fill the deep and yawning vacuum in the ICWU (Irresistible Child-Woman Universe) that had begun with the retirement of Audrey Hepburn from motion pictures. Yes, Natalie Portman was already bursting on the scene, but she was not yet ready to be seen as an object of full-on ICW lust (there was still too much of an inconvenient proportion of Child), unless you happened to be Luc Besson.

But I digress.

The genius of Stiller and Childress is that the entire enterprise is a subversive satire of the conventions of romantic comedy. There is no “other guy shows his true evil colors”. There is no “good guy does something to redeem himself and show he is at last ready for a grown up relationship” in the third act. None at all in fact.

Throughout the entire film, Stiller’s character remains the perfect gentleman, loving, thoughtful, caring, believing in the potential of the woman he loves. Whereas Hawke’s character persists in acting like a total bastard. He insults her, throws tantrums like a three year old, runs away after intimacy, blames her for his own failings, and does absolutely nothing – ever – to redeem himself.

But this is a Hollywood romance, and casting is destiny, so of course she realizes that the slacker/loser is her great love and soulmate. Basically, this film is the ultimate raised finger to everything that’s stupid and unthinking about the idiocy of the Hollywood formula.

You have to hand it to Stiller and Childress. They sailed this right past an entire nation, and as far as I can tell, at the time nobody even noticed what was really going on. Now of course we have seen “The Cable Guy”, “Zoolander” and “Tropic Thunder”, so we know exactly how subversive Ben Stiller is.

I wonder whether this is a kind of identifiable genre: Works of art that shout out their true message to an audience still far in the future – after all, that’s what D. A. Pennebaker was doing with “Don’t Look Back” – a genre that we might perhaps call “Future Subversive”.