On All Hallows Eve, when the moon has come out

The ghosts and the goblins will wander about

You lie awake cowering under your sheet

In your mind’s eye you see where the witches all meet

The Old Sister cackles her dark toothless grin

And summons the revels of night to begin

She traces a sign with one bony finger

And pity the soul who has chosen to linger

As midnight arrives, when the creatures of night

Those long ago fiends, come awake in delight

The ghouls and the demons and zombies arise

Some take to the road, some take to the skies

They head for the town, this terrible host

Demon and incubus, vampyre and ghost

You huddle in bed, you are quaking with fear

For soon all the creatures from hell will be here

They are just down the road, they are coming, it’s true,

And somehow you know they are coming for you

Now they’re downstairs, they have entered your door

You can hear ragged feet as they drag ‘cross the floor

They have caught you at home, in your bed unawares

Is there time to escape? Oh, they’ve come up the stairs

The bedroom door opens — you scream — it’s too late!

You wake up. It must have been something you ate.

Month: October 2011

Plots to take over the world

The topology of the puzzling shape I discussed in yesterday’s post is really fascinating. In some ways it acts like a square, but a very strange square.

Imagine that you lived in a house on a square plot of land. On all four sides you have neighbors, and when you step from your property onto an adjoining property, that neighboring yard seems like a perfectly normal square. So wherever you go, everything appears fine and undistorted.

But the rules for travel are a little interesting, because things act kind of funny at some of the corners. Your neighborhood to the southwest and northeast seems normal — each neighbor shares one other mutual neighbor between them.

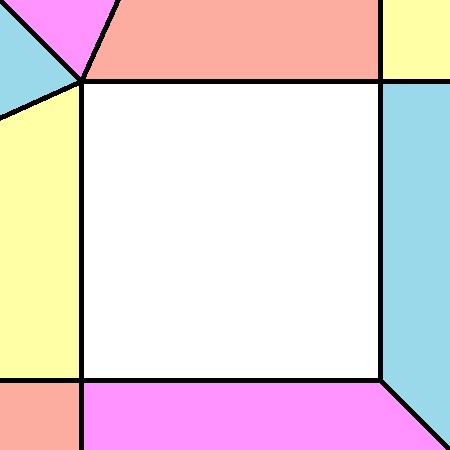

But to the southeast things are a bit stranger. Your neighbors there share a border with each other — it takes only three border crossings and right-angle turns to get back into your own yard. And your neighbors to the northwest have two neighboring yards between them — around that shared corner, it takes five border crossings and right-angle turns to get back into your own yard:

As we already know from the posts of the last two days, the world you are living on consists of sixty plots of land, and the topology of that world is a sphere.

Puzzling planets

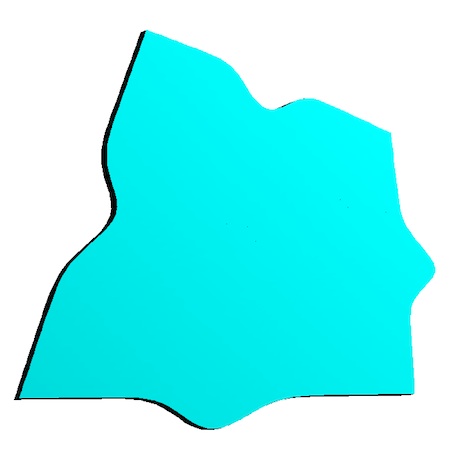

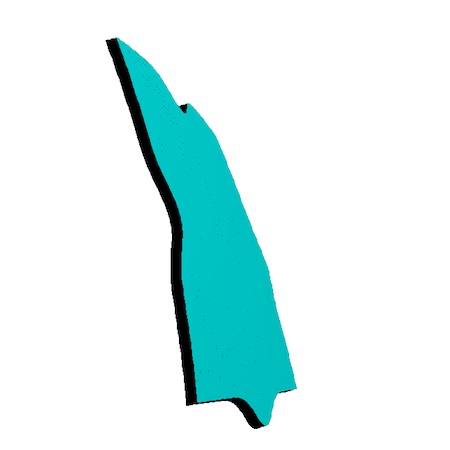

I would like to use my 3D printer to print the sort of patch-work sphere I talked about in yesterday’s post. The first step in doing that is to model the piece in computer software. Below are two views — a front view followed by a more edge-on view, of the software model:

It occurs to me that this would be a great kind of jigsaw puzzle — especially if I modify the edges to make them more interlocking. I did a bit of searching on-line last night to see whether anyone has taken this approach before to designing jigsaw puzzles on spheres, but all the spherical jigsaw puzzles I’ve found are build from a latitude/longitude grid — so the pieces get smaller toward the two poles. Of course the approach I’m describing might already be out there, and it’s just that I couldn’t find it.

If we’re making a jigsaw puzzle, the pieces could form some cool spherical image — the surface of a planet like Earth or Jupiter comes to mind — to distinguish the pieces from each other. Since every shape would be identical, the only way to solve such a puzzle would be through that image.

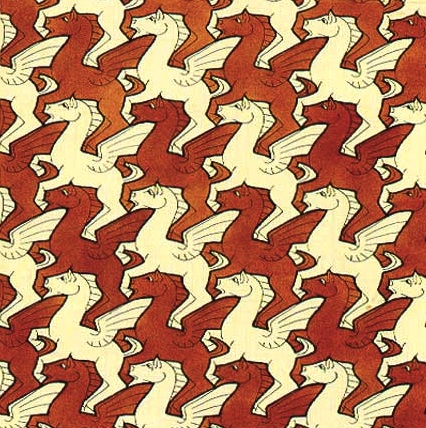

As M.C. Escher pointed out (as illustrated below in his wonderful 1959 work “Flying Horses”), you can change the edges of this sort of tiling — the only difference here is that we are doing this on a filing that covers a sphere:

It would really be fun to design a puzzle shape that matches the theme (eg: “planet earth” or “moon” or “jack-o-lantern”) of the jigsaw puzzle.

The portable sphere

Playing with an icosahedron, and thinking of it as a kind of sphere broken down into simple pieces, got me wondering what would be the smallest piece you could break a sphere down into, so that all the pieces were exactly the same size and shape. That way, if you wanted to assemble a big dome or sphere, you could just carry portable little pieces around with you.

By having all the pieces be identical, you wouldn’t need to worry about numbering or ordering them in any way. Of course you could make a sphere or dome by inflating something, which would also be cool, but I’m thinking of how to make a rigid sphere.

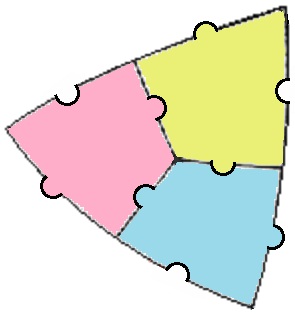

The best solution I’ve come up with is 60 little identical pieces. If you inflate an icosahedron out to a sphere, then you can divide each of its twenty now-curved triangles into three equal pieces, like so:

As you can see from the figure above, we can put little matching protrusions and notches into the edges of each piece, so that they will snap firmly together. Now we have a very compact way to “carry around” a rigid sphere as sixty identical little almost-flat pieces, and then assemble it together as needed. Of course if you only need a hemispherical dome (eg: as a portable planetarium) then you’d only need thirty pieces.

Unless somebody can think of a better solution.

Pipe cleaners

This week I was at a fancy dress-up event where they put things like cool flashing LED lights, watch batteries and pipe cleaners on the tables so all the guests could make stuff. It took me all of one minute to accidentally drop my watch battery, which promptly rolled somewhere far under the table, never to be found again. Which meant my cool flashing LED light would be useless.

And that left me with pipe cleaners. Fortunately, earlier that day I had been talking with Vi Hart, and I thought of her experiments in using household materials to make hyperbolic surfaces (seven equilateral triangles around a vertex instead of six, and you’re in business).

I started folding pipe cleaners into equilateral triangles, twisting them together so they wouldn’t fall apart. Except around every vertex I put five equilateral triangles. So instead of lying flat on a plane (which is what would happen if you placed six equilateral triangles around each vertex), the assembled triangles formed a slight curve.

After I did this for ten minutes or so, gradually adding new triangles, my little sculpture did what any self-respecting collection of equilateral triangles with five triangles around each vertex would do — it formed an icosahedron:

I put my little pipe-cleaner icosahedron on the table, and people were very impressed. Various other guests picked it up, played with it, and turned it this way and that. I suspect they didn’t realize that a shape like that practically assembles itself if you follow the right simple rule. And I wasn’t about to tell them how easy it is to make one of these things. 🙂

I did ask people if they knew how many sides it had. I’m sure that you, dear reader, will get the correct answer right away. Of course the next day I found myself surfing the web learning all sorts of things about icosahedra that I hadn’t known before. And I came up with an idea for another little icosahedron related project. More on that tomorrow.

Reality versus fantasy

Thinking more about the issues that arise from the questionable promotion of the film “Anonymous”, I am struck by the complexity of the social, cultural, ethical and psychological relationship between reality and fantasy. Every society evolves a highly elaborate code dictating when and where everything should lie along this dialectic.

When we read a novel or watch a film, we happily and collectively indulge in a game of “what-if”. In a make-believe world many rules of propriety are suspended. We understand that well-wrought fiction will give us an enormous emotional payoff — a payoff we will pay good money to experience. In such experiences there is generally no confusion about what is reality and what is fantasy. For example, when we watch “Star Wars”, we understand that we are not actually watching an entire planet full of people getting blown up.

In fact, our rules dictating that fantasy experiences do not mix with reality experiences are very strict. For example, for many people in the U.S. it is perfectly ok to go into a restaurant and eat a serving of rabbit or cow. Yet if a real rabbit or cow were deliberately slaughtered to create a scene in a fiction movie, many of the same people would likely boycott the film for ethical reasons. On the other hand, it was generally considered OK for Michael Moore to portray the actual slaughter of rabbits in his film “Roger and Me” — because that was a documentary.

That’s just one example of many. I suspect we can follow the convoluted dance between our perceptions of “reality” and “fantasy” to illuminate all sorts of things just under the cultural surface.

Bernoulli revisited, part 2

I was inspired by Bernoulli’s observation that the higher speed of the air on the top side of an airfoil creates a low pressure zone. The vehicle is then lifted by the higher air pressure beneath the airfoil. My twelve year old brain knew that to make a vehicle fly, I needed to lower the air pressure above the wing surface — essentially, to displace air away from the top — thereby creating a partial vacuum above the vehicle. But there was no rule saying that the displaced air had to end up directly underneath the vehicle.

My crazy scheme was to design a flying machine that would create a partial vacuum on its top surface (which is also what a helicopter does), by displacing the air sideways, rather than downward. The vehicle would be drawn up into the region of lower pressure just above it, and voila, flight.

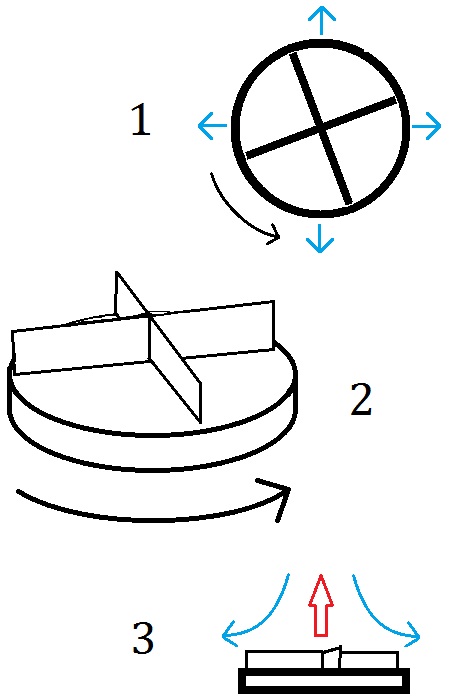

The diagrams below show roughly what I had in mind. The result looked something like a flying saucer — which is not surprising, considering that its inventor was a twelve year old boy. 😉

The top view (1) shows rotors atop the disk spinning, which creates centripetal force that pushes air (the blue arrows) radially outward. The perspective view (2) is a schematic representation of the rotating blades. In practice a lot of work would need to be done to figure out the right size and shape for these spinning airfoils. The side view (2) shows how air comes in at the top and is then pushed out to the side. The partial vacuum above the vehicle results in lift (the red arrow):

In principle, you could stand right underneath one of these flying saucers and not feel any downward wind force. Of course, as they say, theory and practice are the same in theory, but different in practice. I suspect that by now somebody has long since had a similar idea, has probably tried to build one of these things, and has realized why it wouldn’t really work.

But when I was twelve, thinking about stuff like this kept me off the streets and out of trouble. 🙂

Bernoulli revisited

Speaking of Daniel Bernoulli, these last few posts have reminded me of back when I was about twelve years old, and very into helicopters. For a while, Igor Sikorsky was my hero, and I didn’t think it was fair that kids weren’t allowed to have helicopter licenses. Unlike airplanes, helicopters can hover in one place, and to my twelve year old mind, that was just about the most magical thing ever.

I learned everything I could about all things helicopter, from coaxial rotors to gyrocopters to swashplates — swashplates are amazingly clever.

The only thing that really bothered me about helicopters was the downwash. Those huge spinning rotors create a serious downward wind force. If you’ve ever seen people trying to get onto a helicopter while its rotors are spinning, you have an idea how large this force is.

So I set about trying to design something that could hover in the air but would produce no downwash. And it was, in fact, Daniel Bernoulli’s principle that inspired me to think of such a crazy thing.

More tomorrow.

A tale told by an idiot

Note: When I originally posted this, I hadn’t made it clear that my issue with this film is not the film’s premise itself, but rather that the filmmakers are selling it by claiming this fiction to be fact. After very several thoughtful comments by readers — particularly by Phil H — I’m adding this note, and am clarifying the distinction.

Yesterday I obliquely criticized the forthcoming film “Anonymous”, which is based on the inane so-called “Oxford” theory that Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets were written not by him, but rather by the 17th Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere. This is one of those nutty fringe theories that falls apart like tissue paper as soon as you look at the facts. “Keeping the faith” requires the theory’s small but fanatical band of adherents to carefully and pointedly avoid looking at the vast body of evidence that confirms Shakespeare’s authorship. Effectively, subscribing to this particular conspiracy theory is the scholarly equivalent of repeatedly slapping your hands against your ears while loudly shouting “Wah wah wah!”

By claiming their film to be fact, the filmmakers effectively ask the audience to act like idiots. Of course lot of politicians do essentially the same thing, making false statements that are easily verifiable as such. Yet we’re not talking here about politics — which, after all, merely asks citizens to place their liberty, their safety and the fate of their children into the hands of total strangers. No, when we talk about big-budget Hollywood films, we’re talking about something far more powerful — money.

Is it possible that peddling a movie as fact that is based on the silliest possible premise is a deliberate economic decision? Perhaps deep down most people actually enjoy being insulted, and are drawn to movies as a way to be talked down to and patronized. Maybe, behind the scenes, Orloff and Emmerich and their producers actually had design meetings to figure out the most insulting way to sell a movie, knowing that potential viewers would be drawn to a film that offends their intelligence, spits them in the eye, gives them a big slap upside the head, and essentially shouts “You are an idiot” to their collective face.

I guess we’ll find out soon. The film officially opens on October 28, and the box office doesn’t lie.

Anomalous

This week I had the great honor to interview the director Roland Emmerich and the writer John Orloff on their bold new movie “Anomalous”. The film blows the lid off Sir Isaac Newton’s so-called theory of gravity. I managed to catch up with them as they were floating in mid-air, somewhere over midtown Manhattan.

“You’d be surprised how many people think that just because a bunch of scientists say there is such a thing as gravity,” Orloff explained, “then it’s got to be true. We realized at some point that this deference to so-called experts is absurd, and we decided to tell the real story. Right Roland?”

Emmerich jumped in excitedly. “Exactly. You see, Newton was part of a group at Cambridge University pushing this theory that what goes up must come down. We side with a group at Oxford (sometimes called the Oxfordians), who realized that this supposed ‘theory’ was utter nonsense.”

“Did you know,” Orloff interjected, “that Newton was a notorious alchemist and theologian? A theologian. How could a man with that sort of background ever be taken seriously as a scientist?”

“There is a rumor,” I said, “that the two of you had originally thought of making a movie suggesting that Shakespeare didn’t write the plays. Can you speak to that?”

Emmerich snorted and shook his head. “Do you think we’re complete idiots? The evidence that Shakespeare is the author of his own work is so overwhelming, anyone trying to claim otherwise would be laughed right out of Hollywood.”

At this point in the interview, the rope that had been tethering Mr Orloff and Mr. Emmerich to the ground somehow came unknotted, and the two filmmakers began to drift gradually upward into the sky. “It’s ok,” Mr. Orloff called down to me as they floated away, “Somebody will come by with a helicopter to get us back down.”

I didn’t have the heart to tell them about Oliver Stone’s new movie, “Bernoulli was a liar”.