In feminist theory there is a clear distinction between first wave feminism — the original movement that led to women’s suffrage and other rights, and second wave feminism — the more recent movement from the 1960s through 1980s that focused more on rejection of pornography and other cultural manifestations of pervasive domination of women by the patriarchy.

We are now in the era of third wave feminism — a backlash against the reductionism of the second wave. The third wave acknowledges the great diversity among women in ethnicity, in culture, and in religious norms, and seeks equality within this more nuanced and expanded context.

I just started watching the TV series “Lost Girl”, in which the heroine is a succubus, and I realize that our culture is in a third wave of what might be called “supernaturalism”.

The first wave was exemplified by the supernatural as monster, exemplified by Dracula, the Mummy, the Wolfman, the Thing and Frankenstein’s creation. These beings could be sympathetic, but they were always, in essence, the Other — our fears and nightmares manifested as a creature from beyond.

Beginning more or less in the 1960s, our society began to embrace what might be called a second wave of supernaturalism: The recognition that the supernatural creature might have its own normative existence — that from its perspective, it was “self”, and we were “other”. And so we saw such pop culture creations as Bewitched, the Addams Family, the Munsters.

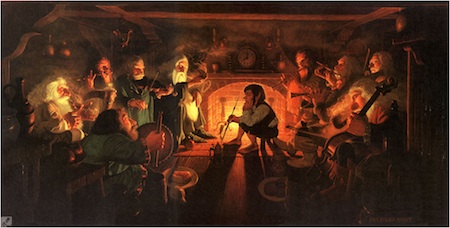

The second wave acknowledged that supernatural beings, like any beings, would see themselves as real, even ordinary, not merely as a creation of our own projections. Seen in this light, Tolkien’s Hobbits were an early pioneer of second wave supernaturalism.

But now, in the era of Buffy, Harry Potter, Twilight, True Blood, Lost Girl and other pop culture creations, we have moved beyond even the duality of human / non-human. We are in the age of third wave supernaturalism, where there it may no longer suffice to label fictional beings in such reductive terms.

Newer fictional universes have moved far beyond mere battles of good versus evil (except as a strawman) toward a more humanist view, in which characters may simply manifest aspects of what could be called “supernatural spectrum disorder”.

Our understanding of the supernatural as metaphor for the human condition has become so sophisticated, so integral to our ongoing cultural narrative, that we now invoke it simply as a useful way to illuminate our own infinite complexity.