In 2003, like many New Yorkers, I attended a protest of our president’s decision to go to war against Iraq (I don’t think most of us were against our country being involved in a war — just in that war). The New York City police routed the crowd of protesters in a very odd way. We were shunted off into various side streets, and eventually quite a few of us found ourselves penned in, so that we couldn’t have left if we’d wanted to.

The mounted police showed up, whereupon policemen on horseback started to charge into the crowd. For the unfortunate people who happened to be in front, there was no way to avoid the kicking hooves of the horses. People were trapped, and some of those trapped people were injured.

The next day, national newspapers printed the police description of the incident. According to the official report, hostile protesters had started attacking the police horses, and the police had done their best to protect the helpless horses from the dangerous and unruly mob.

As you can imagine, it was a very strange experience to be reading something in a newspaper and knowing — from first hand experience — that it was simply untrue. And yet I was aware of the brilliance of the police version of the story. Everyone loves horses, and nasty ruffians (even fictional ruffians) who would attack any of these lovely creatures must be the bad guys.

That was seven years ago. Today the police couldn’t have gotten away with a stunt like this. Too many people in the crowd would be carrying SmartPhones, each with the ability to instantly upload images of what was really happening before the police would ever have a chance to take the phones away.

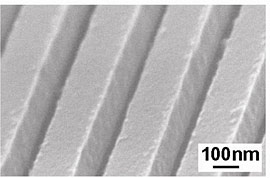

Which leads me to the question of privacy in an ambiscopic world. One objection to everyone having their own ambiscopic display, with anything that you can see instantly streamable to the information cloud, would be the loss of personal privacy within the public sphere. Wherever you go on a city street, somebody will be sure to be recording you, and those recordings can be pieced together to track your even movement — until you enter a private space not occupied by the prying electronic eyes of strangers.

But the incident I described suggests that this might be more of a good thing than a bad thing. Violent crime, acts of hate, police departments descending the slippery slope toward fascist methods, none of these things would be able to flourish in a world where the shared information world is shining a bright light upon the shared public space.

There would still be private spheres, and we would do well to protect them. But it could be argued that a democracy can best flourish when its shared public spaces are exposed to the light, not when they are shadowed in darkness and fear.