There was a time, not too long ago, when putting an electronic auditory enhancement device in your ear was something you did surreptitiously. A hearing aid was something you tried to hide — ideally you didn’t want anyone to know that you needed one. For example, here is an ad for a hearing aid designed to be as invisible as possible:

This is consistent with the principle that people generally try, whenever possible, to appear “more normal”. Since auditory impairment is seen as “less normal”, a hearing aid is viewed as something to hide.

But there has been a fascinating recent trend in the other direction. When a hearing device on one’s ear is seen as a source of empowerment, as in the case of bluetooth hands-free cellphones, people don’t try to hide these devices. Rather, they try to show them off.

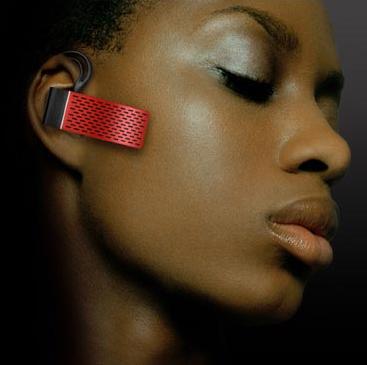

The ultimate current expression of this is the Aliph “Jawbone” headset:

Suddenly it’s cool and sexy to have a piece of hi-tech equipment attached to your ear. I think that the key distinction here is between “I am trying to fix a problem” and “I am giving myself a superpower”. The former makes you socially vulnerable, whereas the latter makes you socially powerful.

This is something to consider when designing an eccescopic display device.