People often talk about the differences between playing a game and experiencing a linear narrative (eg: a book or a movie). After all, when you play a game, you are constantly making choices, whereas when you are being told a story, it seems that you just sit back and passively enjoy the show.

Basically, in most stories, you are introduced to a protagonist, with whom on some level you are asked to identify. You may not like the lead character, but you still identify with him/her. Richard III is a great example of this.

The storyteller poses an overarching moral challenge to your main character, gives him/her some pertinent character flaws to make things interesting, and then the hero is seen to experience a sequence of challenges, along the way generally acquiring some increased level of self-awareness, while you vicariously go along for the ride. So far, it all seems pretty passive.

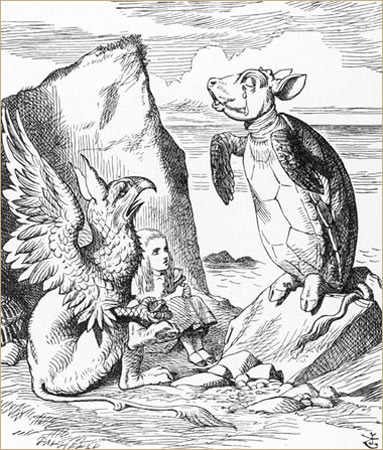

But I would argue that there is actually nothing passive about being told a story, that in fact you are actually being engaged in a particular kind of game. I call this game “hack the character”.

Your enjoyment of the story largely comes from your role as a kind of psychological detective. At every moment of the story you hold some model of the main character in your head. The storyteller’s primary job is to continually drop clues that let you evolve that model in such a way that you might be able to predict what the character will do. If the storyteller does this well, then the challenge will be neither too easy nor too hard. And, in a good story, as the narrative progresses these challenges are gradually made more difficult. And if they aren’t, you get bored.

In other words, you are playing a game.

For example, if your protagonist has invited his colleague Joe over for dinner, and the wife starts acting stiff and awkward around Joe, you might have been given just enough information about the characters to realize, before the hero does, that she’s actually having an affair with Joe. Which sets up the next puzzle, in which you try to predict the exact moment when your hero will discover the truth.

On some level, all readers and moviegoers know that they are being engaged to play this game. For example, the effectiveness of the above challenge is dependent upon our understanding that the story is in fact a sort of game. After all, if this were happening in real life, the wife would most likely be acting stiff just because she doesn’t like Joe, or maybe his politics. But because it’s a story, we know we’re being set up to solve a puzzle, so the rules are different. The moment we pick up the book or begin to watch the movie, we are agreeing to play by the rules of “hack the character”.

In this sense, the greatest storytellers are master gamemakers. Think back on your experience of Shakespeare, Austen, Hemingway, Hitchcock, Woolf, Nabokov, Salinger. Even when they reveal the wheels of the game, spinning away in plain sight, you are still held spellbound, riveted to your seat, turning the page or waiting for the next scene, unable to look away. Because they are that good.

I suspect that when interactive narrative, now still in its infancy, really evolves into a mature medium, that evolution will be fueled by a truer understanding of the “hack the character” game. And I predict that the killer app for interactive storytelling will be the mystery of the human heart.