Yesterday I saw a talk by Scott Ross, who has for many careers helped bring a number of major Hollywood special-effects films to the screen, including two “Back to the Future” films, “Die Hart 2”, “Ghost”, “Strange Days” and “Fight Club”. But in this talk I was alarmed by some conclusions he reached.

Ross was discussing the charmingly quirky Korean 2006 horror/family-dramedy “The Host”, analyzing it from a financial perspective. First he pointed out that the film cost $11M to make ($3M going to out-source the monster effects), while it earned $89M in global box office — a reasonable example of a commercially successful movie.

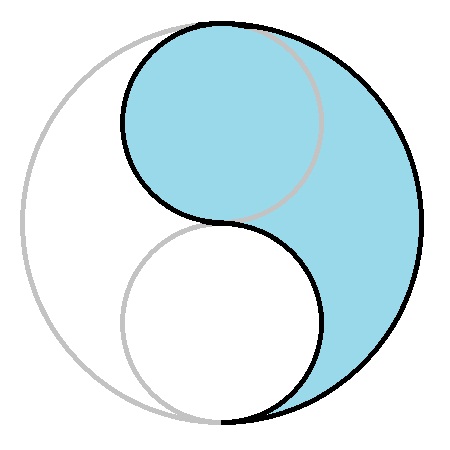

Then he pointed out that only $2M of the film’s box office was from the U.S. From this statistic, he drew the conclusion that the filmmakers had erred — that they should not have released the film in Korean, but rather should have hired a writer to transpose it to English, and make it more culturally relevant to a U.S. audience. If they had done this, he claimed, they would have made a lot more money.

Now, I know that Ross has had a long and successful career in feature films, and nobody can take that away from him. Yet here he was, making a statement that was so wrongheaded, I thought at first that he was trying to make some kind of ironic joke. Sadly, he wasn’t.

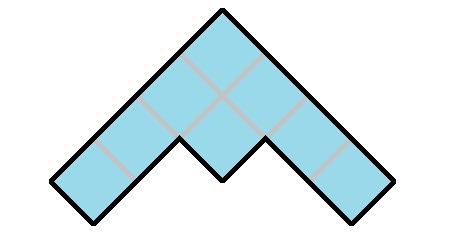

If you actually watch this film (I had caught its initial U.S. release), you realize that its success was due to a unique blending of a very Korean-specific charming domestic family drama with a story that involved a 100 foot long fearsome mutant sea creature gobbling people up for lunch, while those family members fight for their lives.

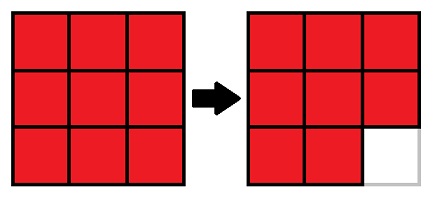

The reason the film works is that these two stories — a tender and gently humorous tale of an eccentric yet loving family and, well, a monster movie — are balanced and played off each other with great finesse. And there are just too many things about the way the film achieves this balance that are culture-specific, for it to be culturally translatable.

I’ll give just one example of many: One of the central conceits of the film, one of reasons in fact that it works so well, is that the threat is real — any of these people can get eaten by the monster, and over the course of the movie a number of them do, even the occasional plucky and adorable youngster. Within its cultural context, this actually strengthens the family drama (you’d have to watch the movie to see how and why).

Imagine, in an American special effects film, a monster actually killing off an adorable child that the audience has been rooting for and has bonded with. You’d be laughed out of Hollywood just for suggesting such a taboo idea.

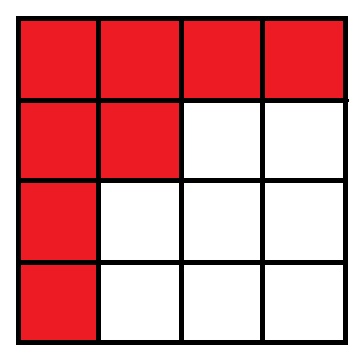

For this and for many other reasons, you could not retune “The Host” for an American audience. Rather, you’d need to make a fundamentally different film. You could give your film the same title, and even the same monster, but you’d have to gut the very core ideas that made the original film so appealing in its original cultural context.

Shorn of the delicate magic of the original writing, your film would not make anything like $89M at the box office — more likely it would make less than $1M. Audiences know when they are being snookered.

The fact that this concept is not understood by someone of Ross’s long experience in film is appalling. No wonder there aren’t more great films coming out of Hollywood.