I’d like to talk more about The Counterfeiters today, and how it is put together dramatically. If you haven’t seen it yet, you may want to do so before reading on.

It’s interesting to examine The Counterfeiters from the point of view of what drives its main character. Basically we are handed a protean individual – he is presented as neither good nor bad, but rather complex, intelligent, unpredictable, enormously charismatic, a seducer and a survivor, a force for both order and chaos. And then he is put through the ringer, severely “leveled up” as they say in computer game parlance – thrown into a whole new dynamic and faced with circumstances more challenging than any he has ever before encountered.

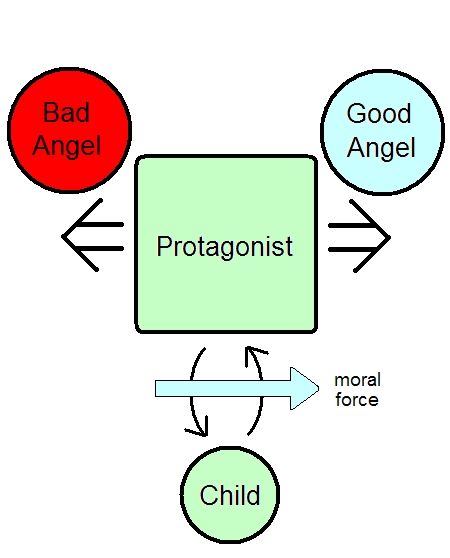

Just as this is happening, we are introduced to two new characters. One serves as a kind of bad angel. This character is suave, charming, in control, seeming to hold all the cards. The bad angel entices our hero to give in to old ways of thinking, to choose seductive moral shortcuts and selfish survival strategies that have worked in the past.

In contrast, the other character – the good angel – is seemingly humorless, an idealist preaching self-sacrifice, representing the pain and difficulty of making the leap to a more grown-up and responsible view of the world.

It is made screamingly obvious to the audience that both of these characters represent aspects of our hero himself. In these two opposing external forces pulling on him we – and he – recognize the two halves of his inner self, battling for supremacy.

And then, in the midst of this war over our protagonist’s soul, a third character starts to emerge. This character is really a child, passive, innocent, dependent, needing only to be nurtured. Not so much a fully fleshed out character as the symbol of one. The protagonist gradually embraces the opportunity to nurture this child, and starts to see survival not merely in terms of taking care of one’s own self, but rather as taking care of the future, of those who need us. The basic set-up is shown in this diagram:

Over time, the protagonist is changed by embracing his role as a nurturer. He realizes that being able to grow, to take care of another, is the way to true survival. This requires rejecting the easy answers of the seductive bad angel, and embracing the more difficult path.

So why does all of this seem so familiar? Perhaps because I’ve just described Juno. It wouldn’t seem that there would be much in common between the story of a womanizing counterfeiter trying to survive a Nazi concentration camp and a sixteen year old pregnant teenage girl in a small town in Minnesota. But in fact both are driven by pretty much the same character engine.

Separated at birth?

In a sense, these two are really the same character, the unformed hero who recognizes the path to spiritual survival only when called upon to be a nurturer. I guess what this shows is not all that surprising: If you start with a solid foundation in how you drive and motivate your characters, you can build a hell of a great story.

By the way, I was only joking yesterday about Americans not telling great stories about outwitting Nazis. Of course there is a long history of American films built upon just this premise, including, among many others, Casablanca, To Be or Not to Be, The Great Escape, and Schindler’s List.

If you’ve never seen the original Ernst Lubitsch version of To Be or Not to Be with Jack Benny and Carole Lombard, do yourself a favor and run out and rent it. See if you can spot the line of dialog from which Woody Allen shamelessly stole one of the best jokes in Annie Hall.