Tonight at Lincoln Center I saw Basil Twist’s riveting and brilliant puppet version of Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka. Thinking to learn more about it, I ended up surfing on-line to wiki.answers.com. There I found a page entitled “Questions with ‘Stravinsky: Le Sacre du Printemps; Petruchka; Firebird; Apollon Musagete'”. On that page I learned all kinds of things about the great composer, such as when was his birthday, how many sisters he had, and what year he composed Petrushka (1910). But I think my favorite question of all was: “Will the same method for removing the water pump on a 1992 Firebird work for a 93 or 94 Firebird?” I suspect that this question would have given even Stravinsky pause.

One thing that struck me, listening to the wonderful music this time, was a feeling that the first melody in its final scene was rather shamelessly borrowed by Cole Porter for the song “Tom, Dick or Harry” in Kiss Me Kate. Does anybody else hear this, or is it just me? According to Wikipedia (so it has to be true, right?) Stravinsky himself adopted this melody from an old folk tune called “Down the Petersky Road”, which suggests that I might just be carping about honor among thieves.

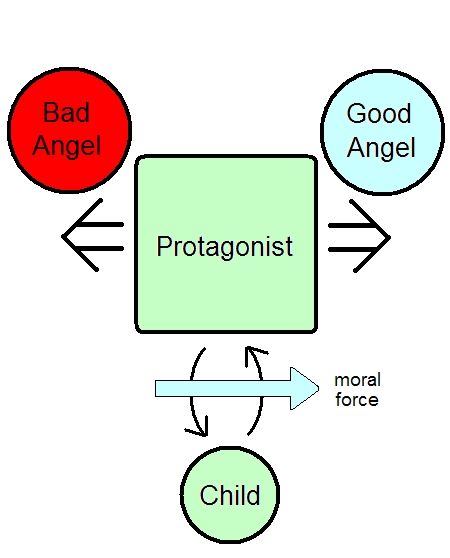

Speaking of honor, another thing that struck me was the strange dramatic resonance of the death of Petrushka, which is in some ways an inquiry into the nature of free will. It could be said that he died for honor, and yet at the same time he died as a puppet, his fate decided from above by a puppeteer’s hands. And that reminded me of an odd conversation I had the other day with a woman I know.

She was absolutely convinced that the guys that she and her boyfriend had recently been talking to in a New York City bar were with the Black Ops – those shadowy elite government forces that we never hear about (although sometimes The New York Times publishes articles about their nifty arm patches).

I asked her what made her think such a thing. She said that all of them were very big and burly, and they kept sprinkling their conversation with references to their trip to Burma and other exotic places. But then, when her boyfriend asked them what they did for a living, they all got mysteriously quiet.

I asked her whether she would really have wanted to know if she was hanging out with an elite squad of professionals trained to go on suicide missions. She thought about it and said no, probably not. But still, she felt that even if they were a secret government suicide squad, they should at least have some reasonable response ready, in case somebody should happen to ask them what they do.

I tried to think of something that they could say, under the circumstances. The only thing I could come up with was: “Well, I could tell you, but then of course I’d have to kill myself.”