Last night I gave a talk to a very diverse crowd, from little kids all the way up to quite older people. As part of the fun, I turned the entire audience into a computer (actually three computers, since the auditorium was divided into three sections, separated by two isles). First everybody wrote down their birthday on an index card (not the year, just the month and day, so as not to put anyone on the spot). Then a beach ball was handed to the person in the left seat of the front row of each section.

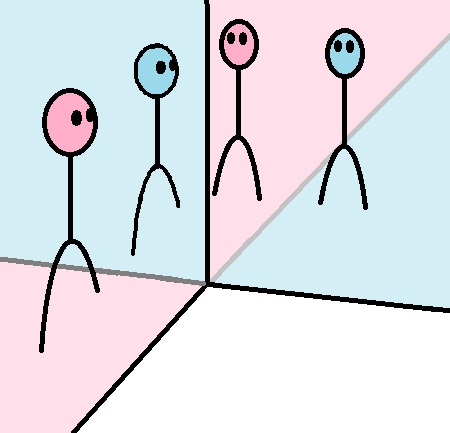

Each of the three sections was turned into one long linear “computer memory” by the following two rules:

- If you are in an odd numbered row (rows 1,3,5,7,…) then your “next person” is the person on your right.

- If you are in an even numbered row (rows 2,4,6,8,…) then your “next person” is the person on your left.

- If you are at the right end of an odd row or left end of an even row, then your “next person” is sitting behind you.

We did a practice run, with each person handing the beach ball to their next person, zigzagging all the way to the back, just to get the order straight. Then the fun began.

I gave everyone the following instructions:

When you get the beach ball:

- If your next person has a birthday that is after yours, then just hand them the beach ball

- If your next person has a birthday that is not after yours, then you both stand up and exchange cards, hand them the ball, and then both sit down.

It took about five minutes for the ball to wend its way from the front to the back of each section. At the end of that time, the person in the very back was holding the ball, and also holding the card of whoever had the “highest” birthday (eg: Dec 28). Effectively, the audience had computed a “maximum” function.

Everyone understood that they could continue using this method to sort all their birthdays into ascending order — passing the beach ball through the crowd over and over again — but that doing so would take a really, really long time.

So instead, I turned them into a parallel computer — with every person in the audience now functioning as a CPU. Under the new rules, we ditched the beach ball, and followed pretty much the same rules as before, except that any audience member could follow these rules any time at all:

- If your next person has a birthday that is after yours, don’t do anything

- If your next person has a birthday that is not after yours, then you both stand up and exchange cards, then both sit down.

As soon as the three parallel computers (one for each section of the auditorium) started operating, there was a huge hubbub of activity. After a while, most of the activity was combined to the middle rows, with the front and back just occasionally coming to life as a ripple of cards exchanged forward or back. After about ten minutes, it was all over. The cards had been sorted.

Of about four hundred people in the room, only one woman ended up holding a card that was out of order. She was very embarrassed to be the only “bug in the computation”, but she took it very sportingly.

Interestingly, three people ended up holding a card with their own birthday written on it. What are the odds?