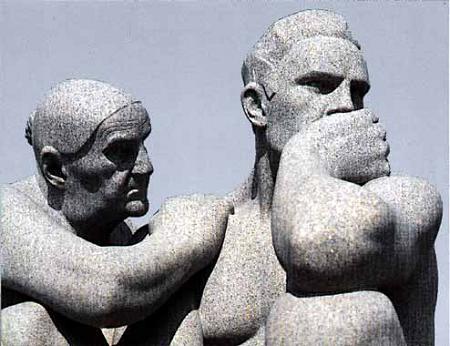

The other day I mentioned Vigeland Park, which is filled with the magnificent sculptures of Gustav Vigeland, and is quite rightly one of the most celebrated works of public art in the world.

The park gives us back a vision of ourselves as noble, larger than life. To walk among its 212 sculptures is to see intimate details within the connections between people – the bond between father and son, husband and wife, two old friends, each moment magnified and honored, celebrating what is best in the human spirit. Not surprisingly, the park is highly visited and is hugely popular among tourists.

But there are many ways to measure the impact of a work of art. The work of Gustav Vigeland is powerful, yet it doesn’t challenge us on a deep level. On the other hand, seeing the work of Gustav’s lesser known brother Emanuel might shake you to the very core of your being.

Quite off the beaten track, outside of the center of Oslo, is a windowless building. It is open only on Sundays, and then only for a few hours. You enter this building in silence through a low doorway, and emerge into a dimly lit space. Gradually your eyes become accustomed to the dark.

You start to see that every surface of the vaulting walls and ceiling is covered by paintings of human figures. But these figures are engaged not in the friendly intimacy of conversation, but rather in all that is powerful and mythic in the human experience – birth, sex, death, all of those aspects of existence that Western religions try to euphemize and defang, here exposed and magnified in all their wildly savage glory.

On one section of wall you see women giving birth, their heads flung back in ecstacy, or holding their newborns aloft in triumph while standing on the gathered bones of previous generations long dead. From another wall emerges the naked bodies of men and women gloriously intertwined in riotous orgies of passionate sex. Further down the wall from these roiling images of life and flesh, half-hidden in the darkness, your eyes eventually find the skeletal figures of the dead, those who long ago had their moment of passion, and must now return to dust.

This work is no affirmation of the individual, but is rather a fierce primal cry of the collected human rush be be born, to procreate, to die and make way for successive waves of onrushing humanity. It is as though you have entered the fevered brain of William Blake, only it has been expanded out all around you, so that you find yourself completely enveloped.

And because this takes place in a darkened room, you do not see these visions all at once. Parts of the wild and magnificent tableau emerge piecemeal, entire sections of a vast and primal story taking shape only after you have been in the dimly lit space for a long time.

The acoustics of the room are such that you need to be absolutely quiet. Any sound, even a scrape or a cough, is magnified many times, ricocheting and reverberating around the room with deafening loudness. And so visitors walk about the space in silent wonder, casting each other looks of astonished revelation as their mind registers some new piece of the vast puzzle.

Emanuel Vigeland’s ashes lie in an urn above the entrance. His greatest work became also his mausoleum, and this is somehow fitting. He does not get many visitors – on a particularly busy day there may be eight or so people at most, wandering silently, at any one time. I was told by the friends who brought me there that at times you might find yourself completely alone in the space.

It is strange how two brothers can be so alike and yet so utterly different. The work of Gustav Vigeland is by far the more widely known – it is public to the point of being iconic. In contract, the work of Emanuel is a dark and secret masterpiece, a brazen outsider challenge to our conventional pieties, hidden away almost to the point of invisibility.

Both are unquestionably works of genius, but only one will rip at your soul, take you out of your daily existence, force you to think about difficult questions that lie beneath the surface of your life. And that is the work that will stay with you.