This is my first post

From an airplane, which makes it

The highest so far.

🙂

Because the future has just started

This is my first post

From an airplane, which makes it

The highest so far.

🙂

If the martians who abducted you bring you back with extra powers, are you alienated?

If you describe your political opponent as a big flesh-eating reptile, is that allegory?

After somebody gives you the drill, are you bored?

If you insist you only like red birds, is that a cardinal rule?

When a song is written about you, are you composed?

After you lose the election to your spouse, do you stay devoted?

When lightning strikes, do you remain grounded?

If I tell you that x times y is a constant, is that hyperbole?

If you refuse medication because you’re already sick, are you being illogical?

If my gloves are on one moment, and then off the next, is that intermittant?

When I run out of the house with wrinkled pants because I have a pressing engagement, is that irony?

If you find a thousand dollar bill, is that noteworthy?

If you hate calculus in one dimension just because you think it’s derivative, are you being partial?

Isn’t that new whiteboard remarkable?

<begin rant>

Some of the comments I received in response to yesterday’s post seem to suggest that there is some legitimacy to what WikiLeaks is doing to the SONY employees, given that some of those employees may have engaged in unethical behavior.

To me, this seems to be not only a highly flawed argument, but precisely the slippery slope to fascism. If somebody at SONY is doing something that might be illegal, that is certainly of potential interest to our law enforcement system. But we do not have rule by mob in this country. A citizen is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

I know it can be tempting to think of “due process” as a mere nicety, but it is actually the bedrock of a functioning democracy. Just because I happen to think that you did something wrong, this does not mean that I get to punish you. If you can simply be dragged out on the street in the middle of the night and branded as a witch, then you effectively have no rights as a citizen.

And it is absurd to say that SONY employees should have known better than to use company emails for personal conversations. I defy you to show me even one individual, among all the people you know, who has never used their company account to write an email with some personal content.

This sort of pretense — that a patently absurd fiction is the truth, and then to attack entire groups of people based on that absurd fiction — is precisely the precondition for fascism. It is what Kafka was writing about. It was also the game plan for a certain ambitious Chancellor in Germany.

It would be a mistake merely to dismiss Julian Assange as an insensitive asshole. He is something far worse: He is the destroyer of discourse, the bringer of fear, the troll who shuts down all useful conversation because everyone is afraid of him.

Sure, some people at SONY have made unethical decisions. As have some people at Google, Microsoft, Apple, Adobe, IBM, Facebook, the U.S. Government, the Spanish government, the Canadian government, the State of Delaware, and pretty much every single organization of significant size throughout history.

That is certainly something we should be concerned about. But it is no excuse to commit an act of violence against entire large groups of people, which is what Julian Assange has done here.

To put it simply, what he has done to these people is disgusting, and violent, and an act of pure terror.

<end rant>

The other day, Julian Assange decided to publicly release an indexed archive of all of those stolen emails of the employees of SONY. If I understand correctly, his reasoning was roughly as follows: Since these people all work for a large multinational corporation, then they must be evil, and therefore they must be punished.

The fact that these people are simply individuals, not powerful multinational corporations, seems to be a nicety that Mr. Assange finds too insignificant to bother with.

I imagine that some who are reading this might disagree with me. They might find WikiLeaks’ logic unassailable. After all, once someone makes the decision to work for a major corporation, shouldn’t they assume that they have given up any claim to moral legitimacy? Shouldn’t they expect that stolen information about them and the people in their life will be made public and conveniently indexed, that their every personal conversation will be come a matter of public discussion and perhaps public mockery?

The fact that these employees’ children, their spouse, their friends, everyone in their personal circle will be forced to witness their private life made public, isn’t this simply righteous punishment for the unforgivable act of being an employee of a major corporation?

If you do agree with Mr. Assange on this one, then I hope you realize you have a moral obligation to gather up every intimate and personal email you have ever sent or received, and send it immediately to Mr. Assange to do with as he will. After all, if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.

I have a disturbing image in my head of Mr. Assange gleefully urinating all over these peoples’ lives.

Maybe that’s why they call it WikiLeaks.

A really good comedian can bring a roomful of people to tears of laughter. We think of humor as one of the most uniquely human — and precious — legacies of our genetic inheritance. Shared laughter ties together people of all walks of life, all ages and economic circumstance, and it helps us realize our connection with each other.

What about an artificial intelligence? In a funny twist on the Turing test, would it be possible to create a computer program that could be as laugh inducing as a really good comedian?

What would it mean if such a machine were to exist — the first truly funny cyber-comedian? I mean, one that could play to packed houses, and slay them every night.

Would we feel that something sacrosanct, something uniquely human, had been lost?

Or would we just laugh, when we realize that the joke is on us?

One day, perhaps not that many years from now, we will hold even our most ordinary conversations with the aid of very advanced software. We won’t be thinking about this software at all. It will just be doing its business quietly, turning real-time images of our facial expressions and body movements into emotive avatars that help to convey the subtleties of our communication across the world, perhaps representing us as virtual avatars.

The appearance of these avatars may vary, depending on the social or professional situation. We will think of them the way we now think of clothing: We wear them not to misrepresent ourselves, but rather as a kind of adornment, a way to better convey which side of our selves we are trying to bring to a particular situation.

One side effect of all this is that our every movement and facial expression will be tracked, and can be retrieved later for playback. If privacy laws are properly set up, random strangers will not be permitted to invade our lives by re-playing our every moment. But we ourselves certainly will be.

And that brings up an opportunity — one that is more or less new in human existence. We can examine, post facto, how we have expressed ourselves to others. If we became angry in a social situation, or acted awkwardly, we can use such recordings to learn how to do better. In ways never before possible, we will be able to hold an informed mirror up to ourselves, and perhaps improve our ability to communicate and share our feelings with others.

Instead of simply experiencing l’esprit d’espalier, the missed opportunity to say what we really meant to say, or to properly channel, in the heat of the moment, unexpected feelings of fear or distress, we will be able to look back on those moments, and perhaps learn from them.

This evening I had dinner with an old friend. The last time we had seen each other, we had both been much younger than we are now.

Fortunately, he has not aged a day. Which is great, because according to my friend, neither have I. 🙂

I gave a talk this evening about the possible future of shared virtual reality, to an audience of fellow VR enthusiasts. Everyone was very knowledgeable, and enthusiastic, and open to possibilities.

It was one of those talks where the feeling in the room is very positive, and we all end up grooving on the moment. I realized that I was drawing energy from the room, and that the people room were in turn drawing energy from me.

And I couldn’t help wondering whether such a feeling would be possible in a shared virtual reality. This sense that we had, that we were in a unique time and place, in a moment that mattered, this electricity that we were somehow all communicating with each other through our shared physical presence, could it be replicated on-line?

One gauge of shared VR might be whether it gives us the same feeling that we get when we are in a physical room together sharing a moment.

Wouldn’t it be ironic if that level of shared presence turns out to be unattainable?

If I were the head of a large high technology corporation, I’d be looking at the bottom line. And the bottom line ultimately rests on I.P. What do I own that my competitors do not?

That doesn’t give me a lot of room to fool around. If I direct my resources to focus on initiatives that won’t come to market for another twenty years, I am essentially dissipating my advantage.

In particular, if our company applies for patent protection on those initiatives, we are essentially just giving away valuable know-how to future competitors, since the patent will expire around the time anybody will benefit. It’s not a very good strategy.

On the other hand, if I am a young researcher at a University, I am not in a position to capitalize on technological innovation in any large scale way. The most important resource I have is complete freedom to pursue directions that others are not yet pursuing.

I probably won’t be rewarded for those pursuits with vast riches. But I will probably be rewarded by a life of complete intellectual freedom, as well as the steady financial support of large corporations that know full well the value proposition at work: If they keep lines of communication open with people like me — and with my students — then they will have an insight into what might lie just beyond the commercial horizon, and they can start preparing for whatever that may be.

When you zoom into a Google map, you are using my algorithms. When you play Minecraft or Diablo III or Worlds of Warcraft, you are using my algorithms. When you see a Science fiction movie, or an animation by Dreamworks or the Walt Disney company, you are seeing my algorithms at work.

In all these cases, you are mostly seeing the benefits of initiatives that I and people like me started long ago. And for the most part, we are no longer working on those things. We are busy working on things that you will benefit from in another fifteen or twenty years.

While it is understandable that Vasco wouldn’t know all this, it is very helpful that large corporations are keenly aware of it. And those corporations make sure that our University research labs get the funding we need to keep doing whatever we think needs to be done next.

They never tell us what to work on. But they are always extremely interested to see what it might be.

I’ve been thinking about the following comment by Vasco on my post the other day about the relationship between University research and the research done at for-profit corporations:

P(You spending time) << P(google spending time) P(You doing research) << P(google research rezults)

It’s weird to me that people might think this is actually the relevant concept. Because it doesn’t come even close to describing the underlying value proposition.

When you use Google maps, and a server smoothly delivers a collection of power-of-two resolution image tiles that your web client then assembles into differently scaled views, do you really think that those algorithms originated at Google?

It is rarely the case that the fundamental work behind a product originated at a major corporation. Major corporations exist primarily to develop techniques and approaches into robust and viable products — a process which takes an enormous amount of focus and hard work by many people. Those corporations do not exist primarily to be the source of entirely new concepts.

The thing that Vasco is not taking into account is when time was spent, and the cumulative power of the decades of influences from the time an idea was first introduced to the time when it it ready for commercial deployment.

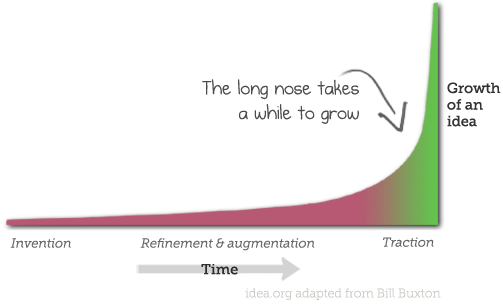

More on this tomorrow. But meanwhile I will leave you with a brilliant chart by Bill Buxton, which will be the subject of tomorrow’s post: