Imagine looking into a room where everything looks completely ordinary. But when you look into the mirrors, then all sorts of spooky things appear about the room — images, faces, writing. This could be an interesting way to tell an immersive ghost story.

You could do such a thing using circularly polarized light. In ordinary linearly polarized light (as in many sunglasses and projectors), all the light waves vibrate at the same angle. But in circularly polarized light, the light waves spiral — either clockwise or counterclockwise.

Most 3D movies are shown with linearly polarized light. When you wear those funny glasses, the filter over your left eye shows only polarized light slanting diagonally one way, and the other shows only polarized light slanting diagonally the other way.

This works fine as long as you don’t tilt your head to one side or the other. If you do that, then the angles don’t line up anymore, and each eye ends up seeing both images, which ruins the effect.

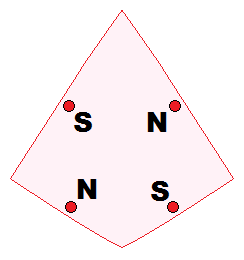

Some more expensive 3D projection works with circularly polarized light. The left eye filter sees only light waves that spiral one way (say, counterclockwise), and the right eye filter see only light waves that spiral the other way (say, clockwise).

And the effect works just as well even if you tilt your head. In fact, you can rotate each filter all you want, and everything still works, because the light waves are still spiraling in the proper direction.

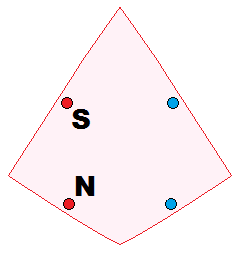

OK, here’s the really cool part: When you bounce linearly polarized light off a mirror, you just get the same linearly polarized light back. But if you bounce circularly polarized light off a mirror, the reflected light switches orientation — clockwise turns to counterclockwise, and vice versa.

You could make some really interesting installations with this. For example, imagine looking into a room, through a window that lets through only clockwise circularly polarized light. Counterclockwise circularly polarized light projected onto walls and statues in this room would be invisible. But if you looked into the mirrors in that room, then all of those projected images would become visible.

Imagine the artistic possibilities!