If you start from scratch, aiming to create the most efficient possible thumb-chording that does not require looking at your SmartPhone, you can do a lot better than Braille. For example, let’s start with the fact that over 75% of all characters typed are one of SPACE,E,T,A,O,N,R,I,S,H,D,L,C,U (roughly in descending order of frequency).

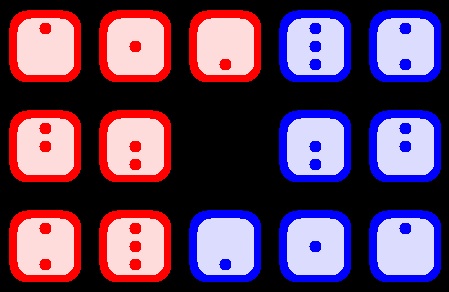

We can use the entire SmartPhone screen to lay out a 5×3 thumb keyboard with the following arrangement:

| E | U | C | L | T |

| → | O | H | S | → |

| A | I | D | R | N |

This keyboard has already taken care of more than 3/4 of all the characters you’ll ever type (we include two ways to type SPACE because it’s by far the most frequently typed character).

We can then get an additional 75 additional characters by “chording” with both thumbs at once, with the left thumb on one of the three left-most columns, and the right thumb on one of the three right-most columns. 75 characters is far more than needed to type all the letters, digits, punctuation and special characters on a keyboard.

I think this keyboard is going to be very fast to type on. Since all the other characters after those first 14 are used much less frequently, having them as two-thumb chords won’t slow you down very much.

Not only does this arrangement allow non-sighted people to type quickly, but it can also be used by anyone in a situation where you need to type quickly into your cellphone without looking at it (eg: during a meeting).

As is usual for keyboards for the non-sighted, there would be a tutorial mode that allows you to drag your thumbs over the keyboard to sound out each character.