There are things in this world that are stupid, other things that are absurd, and then there are things that are so head-spinningly inane that you just gaze in awe, and even a kind of grudging respect, as your befogged brain realizes that it is witnessing a form of high art – sheer perversity raised to such a pitch of exquisite ridiculousness that the universe itself must be shaking in a deep rumbling jelly roll of laughter.

Yesterday I read an article in The New York Times about what was described as:

the “beautification engine” of a new computer program that uses a mathematical formula to alter the original form into a theoretically more attractive version, while maintaining what programmers call an “unmistakable similarity” to the original.

I hasten to say, at this point, that comparing a particular face to a statistical norm to study individuality versus “beauty” is very old news. Susan Brennan, who long ago moved on to research into psychology and spoken language, did exactly this comparison in her ground-breaking 1982 Masters thesis.

I had already known about the particular work in the Times article, since it was presented as a research paper at the ACM/SIGGRAPH conference this last summer. But I had sort of ignored it. Of course it’s based on a set of cultural assumptions that should turn your stomach (and if not, then what on earth are you doing reading this blog??). But in a kind of reverse ju jitsu of politically correct open-mindedness, I had convinced myself that if people really want to spend their time figuring out how to turn images of people into pretty mannequins, who was I to argue? At least none of that research money is going to build weapons that kill people.

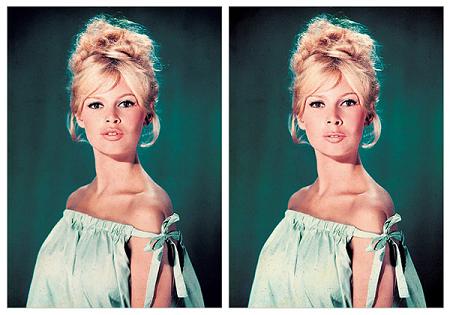

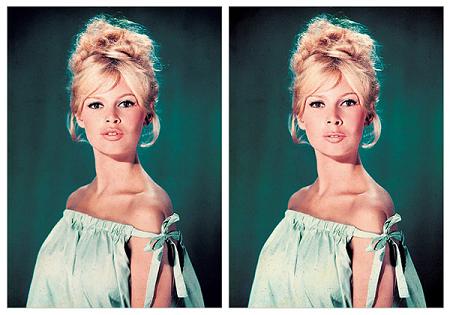

But then I saw, in the Times article, the following before and after image, in which the “beautification” algorithm was applied to the face of the young Brigitte Bardot:

And that’s when the utter nuttiness of this quest struck home. Who in their right minds would turn one of the most beautiful and alluring sights in the history of humankind – the face of the young Brigitte Bardot – into what can only be described as a bad impression of Barbara Eden as reconstructed by Martians?

As I said earlier, I am impressed with the sheer perversity of this goal. It’s like that episode of the old Superman TV show in which an eccentric-genius scientist invents a machine that can create a pound of pure gold. The only catch is that to do this, the machine requires a pound of pure platinum. The hapless crooks who steal his invention almost go broke before George Reeves puts on his Superman costume and shuts them down.

I am as open-minded as the next fellow. Readers of this blog will recall that – in a fit of graciousness and extreme generosity – I recently entertained the hypothesis that Sarah Palin is not actually the head-thumpingly blithering and drooling idiot that she publicly and embarrassingly projects every time a microphone is shoved in her face. And I got a lot of flack for that generosity by my readers, let me tell you!

But enough of Sarah Palin – we were discussing serious things. What I think when I look at the above “before” and “after” images is that they are reversed. The scary Barbara Eden mannequin on the right forms a kind of aesthetic void – an absence of anything vulnerable, interesting, intelligent, sexy or lovable. It is the visual refutation of your very individuality as a human, as though George Orwell’s Big Brother had finally managed to worm his way into your soul, rip it out once and for all, and replace it with slogans like “Love is Hate”, “War is Peace”, “Freedom is Slavery”, and “Ignorance is Strength”. Oh wait, I’m sorry – that’s the 2008 Republican presidential campaign platform. My mistake.

What is the interesting lesson we can take from this bizarre exercise in aesthetic erasure? What non-trivial research question we can ask? I think it is this: What happens when we reverse the two images? Given the disturbingly bland image on the right, could we somehow transform its obscene nothingness, breathe life into it, and produce an image of the young Brigitte Bardot? What are the magical elements within Mlle Bardot’s enchanted countenance – elements missing from any mere cookie-cutter fashion model – that make us fall in love with her? What, exactly, are the quirks, the inimitable flaws and imperfections, that convey her true beauty? That convey anyone’s true beauty?

That’s what I want to know. And that, I think, would be worth studying.