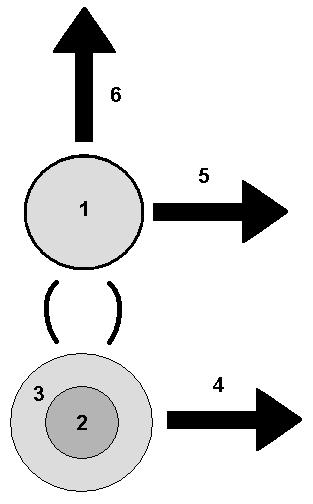

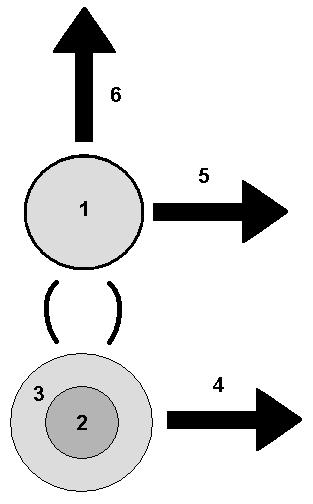

When you play a computer game, what are you learning? And how can we describe the essential pieces of that learning process? My colleague Jan Plass, whose research studies the effective use of technology in education, and I have been having some pretty fascinating discussions and spirited debates about how a game can function as a kind of vehicle for learning. One intriguing problem is how to visualize this vehicle in a way that clearly shows how all of its parts work together. Here is one such visualization:

- Player’s understanding – ability to play well

- Game mechanic – the rules of play

- Aesthetic design – graphics, sound, etc.

- Narrative drive – the “story” moving the game forward

- Extrinsic rewards – points, winning, etc.

- Intrinsic rewards – getting better, improving skill

Everything revolves around the interplay between (1) the model in the player’s head and (2) the mechanic of game play. All of the other pieces are in support of that interaction. Graphics, sound, and so forth (3) serve to add clarity and aesthetic pleasure to the experience, but they are really scaffolding to support that central player/game-play dynamic.

Similarly, a game generally provides some sort of narrative thrust (4), such as “get three in a row”, “capture the enemy king” or “buy up all the real estate”, which helps to focus the interaction in the player’s mind by giving it context.

In addition, the player is rewarded for good play in two ways: extrinsically by earning points, winning games, being the high scorer among a group of peers, and so forth (5) and intrinsically by gaining improving in skill, confidence and ability to take on more advanced challenges (6). In many computer games this increase in skill is often rewarded by “leveling up” – a case where intrinsic reward is augmented by an extrinsic reward.

A game that does not continue to give intrinsic rewards would soon grow tiring. This is why, for example, only small children enjoy tic-tac-toe: Because the highest level of attainable skill is quickly reached by older children and adults, and then there are no more opportunities for intrinsic reward.

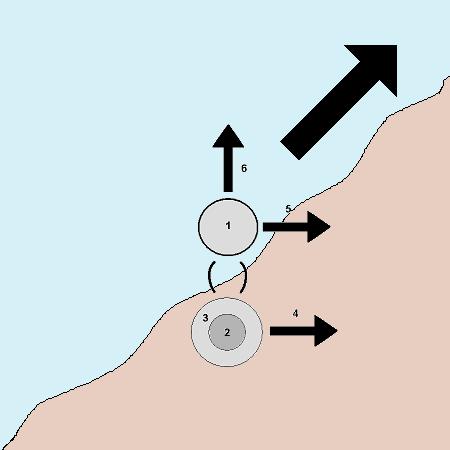

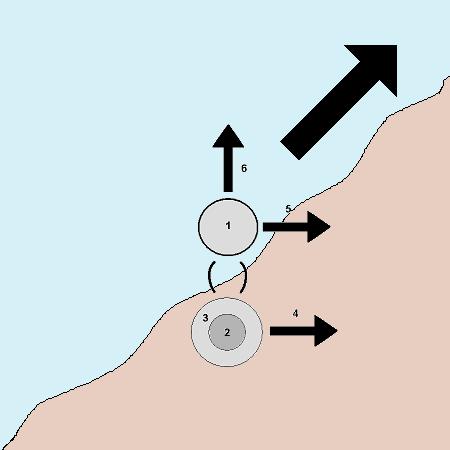

The entire above model only really makes sense as a support vehicle to “move” the player’s mind, through a path of maximum fun, in a way that provides continual pleasurable challenges. This tends to result in ever increasing skill, as long as the game lasts. This path of maximum engagement, neither too easy nor too difficult for the player’s current skill level, corresponds to the mental state that Mihály Csíkszentmihályi refers to as “flow”.

One can visualize this as a landscape with an optimal slope. Game narrative and extrinsic rewards move the player and the gameplay forward, while the intrinsic reward of the player’s progression in ability moves the entire structure upward along the slope:

As the entire vehicle moves, the nature of all the components within it might be changing as appropriate: the player’s mental state, the nature of the gameplay, the aesthetic components, the narrative of the game and the rewards offered, both extrinsic and intrinsic.

A good game is one that moves this vehicle along this upward terrain by evolving all these components appropriately to maintain a maximum sense of fun challenge.

It could be argued that the only difference between a good game and a good educational game is in the opportunities for knowledge transfer of the intrinsic rewards (6) out of the game and into other contexts. For example, a rewarding experience playing Worlds of Warcraft can increase a player’s abilities in the “science” of alchemy. But one could well envision an alternate version of WOW with exactly the same gameplay, yet which challenges the player to improve his/her skills in chemistry or some other skill that transfers well to the world outside of the game. That version of WOW could indeed be an effective educational game.