Today I flew from Seattle to St. Louis, because tomorrow I’m giving a talk at Washington University. Imagine that – going from one Washington to another in the same day, and neither one our nation’s capital.

My friend and host Caitlin cooked me a delicious dinner (pasta + sun dried tomatoes + garlic + olives + chickpeas + various subtle spices), and that reminded me of the very first time I tried to cook for my parents, after I was out of college and I’d gotten my own apartment and a real job.

I figured that it was an important step – showing my independence by doing something nurturing for my parents – taking care of them for a change. I assiduously followed the cookbook, got all the right ingredients, preheated things, chopped other things, and timed it all out so that my meal would be ready to serve by the time my parents arrived.

I only made one mistake.

I think it was an understandable mistake. After all, I’d never really cooked before. It’s not like I could be expected to know all of the technical terms right out of the gate.

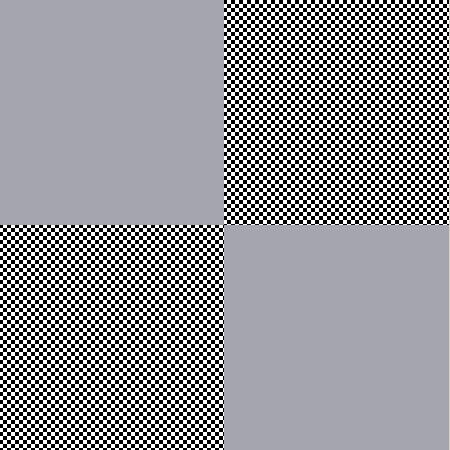

To be more specific, it turns out that this:

is not a clove of garlic. Those of you who, like me in my tender youth, have naively thought that the above thingie is a garlic clove are in for a rude awakening. In fact, it’s something called a “bulb”. When you open up a bulb you get about ten little slices, like pieces of an orange. Each of those little slices, like the thing below to the right, is a garlic clove:

Why is this important? Well, when a recipe calls for two cloves of garlic, and your parents are coming over, and you have prepared them a dinner into which you have actually incorporated two entire bulbs of garlic (around twenty cloves, by my reckoning), things are likely to go amiss.

Fortunately my friend Burke happened to come by some time before the arrival of my unsuspecting parents. Unlike me, Burke actually knows a thing or two about cooking. He had me sautée and sautée relentlessly, which didn’t exactly rescue the meal, but considerably reduced its near-lethal strength.

Needless to say, the entire apartment – and probably all who ate there that evening – reeked of garlic for the next week. My mom and dad were very gracious about it, and they gave an excellent impression of enjoying the meal. It’s amazing what some parents will do out of love for their children.

But there may be a silver lining to this episode: You have probably heard that vampires hate garlic. And I can say definitively that from that day to this, I have never – not even once – been attacked by a vampire. I suspect that my good fortune in this area has been entirely due to the lingering effects of that meal.