The 1917 song I’m Always Chasing Rainbows, by Harry Carroll and Joseph McCarthy, borrowed its melody from the middle section of Frédéric Chopin’s 1834 Fantaisie-Impromptu in C-sharp minor.

There have been many recordings of this wonderful song by everyone from Bing Crosby to Alice Cooper, but perhaps my favorite was the achingly sad rendition by Judy Garland in the 1941 film Zeigfeld Girl.

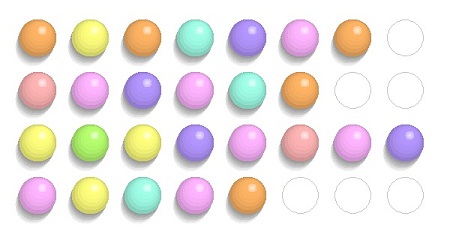

One of the things that intrigues me about the candy buttons representation of music is the way it blurs the distinction between musical score and musical instrument. I’ve transcribed the first few bars of I’m Always Chasing Rainbows onto a strip of candy buttons. The image below links to an applet that lets you play the song by moving your mouse across successive rows of candy buttons (it’s up to you to play with the correct rhythm).

Or you can roam your mouse freely over the applet, using the score as a kind of musical keyboard, to create your own melodies. The original melody you create will be a kind of collaboration between you, Harry Carroll and Frédéric Chopin.

Happy rainbow chasing!!!

I love it when songs reference other songs, especially when the references are to classical music! I listened to both the Chopin and the Judy Garland. It’s really cool to hear the familiar tune!

Is there a particular reason why you chose to modify the original melody in your rendition? The C sharp (red) on the second line, the F sharp (green) and C sharp (red) on the third line are all half a step down in the original.

Thanks Xiao for catching that error! At some point I switched from a diatonic to a chromatic pitch table, and I did without paying attention (never a good idea). It’s fixed now, thanks to you!!! 🙂 🙂

It’s interesting that the red and the green looked out of place in addition to sounding out of place. All the other notes were nice pastels, and the darker colors stuck out like sore thumbs.

I think that in this case, it’s a result of the key in which you chose to transcribe the piece. I like how using colors to represent tones could generalize this occurrence across keys. For instance, you can easily spot the accidentals, blue notes or tension notes in a line, or even key changes.

It might a bit of a special case, arising from the my decision to design all of the white keys to be pastels, and the black keys to be dark intense colors.

This piece is in the key of G major, which has only one black key — F#. But in the melody, the second note on the third line is flattened to the minor seventh — ie: F natural — so in my color scheme it shows as pastel green rather than dark green.

I do agree that once somebody gets used to this scheme, any given key signature will start to jump out at them, and chromatic flourishes will stand out. But for beginners, that will only happen in a key signature with all white keys, such as C major.

To achieve what I was talking about across all keys, colors would probably have to be assigned relatively to tones rather than absolutely as in your system. The colors would then serve as an auxiliary source of music theory information that could be especially useful for beginners to see chord progressions in a piece.

By the way, should the last D on line 1 be raised one octave?

That’s an excellent thought Xiao — make the colors relative to the key signature and use them to supplement other cues. That’s actually very much in the spirit of your MirrorFugue research!

And thanks for catching that low/high D note. You can proofread my work anytime. 🙂