Four days ago I deliberately avoided the obvious post, as some of you may have observed. I was hoping someone would notice and comment, but alas, nobody has. In any case, June 6 just seemed far too easy a target. The timing was too precise – to the letter, so to speak. But today I make up for my earlier circumspection by adopting a deliberate numerological laxity. Throwing all caution to the winds, I give you the letter H.

And a good day for it too. Today is the tenth day of the sixth month. Being that the average of 10 and 6 is 8, this is a wonderful day to introduce our eighth letter – a letter so important they named a bomb after it. This fine figure of phonetic fun facilitates a fertile font of fabulous facts. First, consider the numbers. H stands for Hydrogen, which is element number one. Yet to write the lower case h you need two strokes, whereas to write the upper case H you need three.

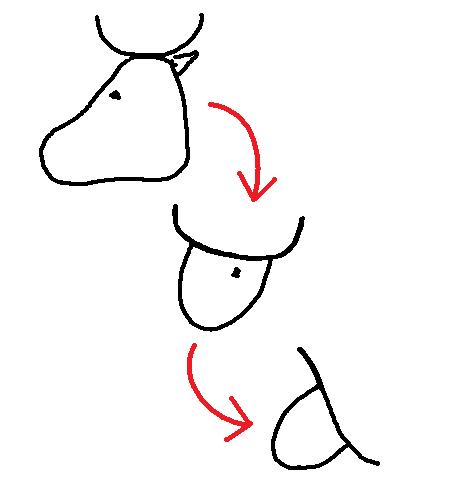

But what is the connection between H and the number four? I don’t know about you, but I have always found it somewhat disturbing that 4H Clubs and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are both equestrian organizations symbolized by the identical combination of number and letter. Mere coincidence?

In Monopoly a Hotel is worth five Houses (both great H words), and in geometry a hexagon has six sides, whereas a heptagon has seven. Which brings us back to eight.

I could go on like this all day, but I won’t. There are more interesting things to talk about. Like the fact that H brackets all of our metaphysical possibilities – it stands both for the place most people are hoping to go when they die, and the place they’d least like to end up. Famous people seem drawn to it as well: Hubert Humphrey, Hal Holbrook and Harry Houdini. Not to mention Halston, Homer, Hadrian, Henry Hudson and Herbert Hoover, to home in on just a handful. Must be something in the H2O.

But wait, there’s more.

For example, did you know that to Johann Sebastian Bach the letter H was the eight note of the musical scale? Actually, in his day “B” was the German name for the note that today we would call “Bb”, whereas “H” was their name for the note we would call “B” (got that?). The cool thing about this is that Bach was therefore able to compose a fugue based on a melody spelling out his own name: B – A – C – H. If you wanted to sound this out on a piano using today’s notations, you’d play Bb – A – C – B.

How many great composers in history have been able to work their own name into a musical theme? Imagine the jealousy of all those long named composers like Tsaichovsky and Shostakovich! Yet I somehow doubt that Bach was the only musical innovator with this idea. For all we know, there might be melodic messages lurking within the music of the Dada movement, or the songs of ABBA, not to mention the indie rock band Bede. Or even handy notes to housekeepers hidden by hipster rock stars, like: “A FAB CAFE HERE, FEED DAD – EDGE”.

Horrors.